Limitations in Quantum Theories of Mind (WIP)

Note: I never found the original markdown file for this paper. I might eventually fix all of the formatting.

Introduction and Theories

In Descartes’ Meditations he attempts to make a logical analysis to demonstrate the possibility of knowing some grounding principle for all knowledge. In the work, he demonstrates that while it is possible to doubt the existence of one’s body, it is impossible to doubt the existence of one’s mind. Using the principle of non-identity, Descartes concludes that the body and the mind are ontologically separate entities. Though his intent was mainly to argue against epistemological skepticism, Descartes ushered in a lively debate over the interaction between body and mind. All of the major theories of mind share distinct problems in their account of the nature of body and mind. Descartes’ view, Cartesian dualism, is problematic in that it must posit unknown physico-pyscho and psycho-physico laws through which body and mind interact. Reductive physicalist theories hold that mental states simply emerge from physical states, but this is hard to square with common experience. Finally, idealist theories attempt to reduce physical states to mental states, which seems impervious to any scientific investigation. Quantum theories however, may prove extremely helpful in plugging these gaps in each of the major theories of mind. Specifically, non-locality helps explain how entities might interact without physical contact, and subatomic particles may help explain how body and mind could be reduced. Unfortunately, the scientific data upon which quantum theories of mind rely are widely open to interpretation. Before delving deeper I will briefly explain several theories of phenomenal consciousness which could be bolstered by a quantum theory of mind.

Dualism is traditionally associated with Descartes, but the strength of his account means that many contemporary theorists hold to some form of this theory. Qualia are difficult to account for in a reductive model, but easily explained with a dualist model. If Howard eats an apple, he has a certain experience of the apple’s texture, taste, and smell. Not only does Howard have an experience with certain phenomenal character, all of these sensations are experienced as a coherent whole. It is possible to imagine another world in which the physical characteristics of Howard’s body are totally different but his phenomenal experience is identical; such as a brain in a jar. The example of the brain in the jar provides strong evidence that mental states are not dependent on physical states. The principle of non-identity holds that if something can be said of one thing that cannot be said of another, the two must be separate entities. Since one can say a body is extended and physical, but a mind is not extended and physical, the two are separate. One final strong argument for dualism is the body survivability argument. The cells that make up a conscious being, importantly brain cells, are constantly being replaced. Despite the constant replacement of physical matter, conscious experience is stable and connected to the entire life-history of the organism in question. Since matter is constantly replaced without breaking the continuity of mental experience, it seems plausible to say that mind and body are separate. These arguments for dualism are difficult to overcome and therefore present difficult opposition to reductive theories.

Despite the seeming strength of Dualism, its necessary conclusions shed doubt on the veracity of the theory. Mental causation is especially difficult to explain with a dualist theory. When Howard eats an apple, it is readily apparent that his phenomenal experience is tied to the physical characteristics of the apple and his body’s response to those characteristics. Additionally, Howard’s conscious thoughts about the world cause his body to move and put the apple in his mouth. Since the physical characteristics of the physical world and Howard’s body impact his phenomenal experience and vice versa, the two are causally linked. The mind and body therefore, cannot be entirely separate. Additionally, the “new problem” of mind-body interaction states that in light of the fact that physical brain activity maps to mental experience, there are three implausible conclusions to dualism. Presumably, if one knew exactly how the brain worked and had perfect knowledge of a subject’s brain activity they would have perfect knowledge of the subject’s thoughts. Either some physical events cannot be explained in physical terms, physical events are overdetermined by mental and physical causes, or mental states do not cause physical states. Each of these conclusions seems counter-intuitive. Foundationally, the issue with dualism is that it cannot account for interactions between body and mind without the addition of some unknown process.

Behaviourist and identity theories are physicalist theories of phenomenal consciousness that avoid the problems of dualism by relying upon observable data about conscious beings. Physicalism does not rely on what JJ Smart calls “nomological danglers.” concepts like a ‘mental realm’ which cannot be investigated and are not distributed throughout reality. 1 Behaviourists hold that to be in a mental state means to engage in or be disposed to engage in a behaviour. On this account, to be in pain only means to engage in or be disposed to engage in behaviours like crying, yelling, or tending to a wound. Behaviourists do away with the problems of dualism since they do not need to posit a “realm” of mental experience separate from observable behaviour. This theory though, cannot account for differences in behaviour between conscious beings with the same or similar phenomenal experience. Though Howard and Wendy might experience the same pain, they could behave, or be disposed to behave, in totally different ways. Identity theorists hold that to be in a mental state is just to be in a physical state. On this account, the experience of seeing a car drive by just is the activation of V5 neurons. The problem of multiple realizability with identity theory is the issue that physical states like V5 activation cause different phenomenal experiences in different conscious beings. Wendy has a different experience of the car than Howard. For behaviourist and identity theories to hold, there must be some way of explaining how physical reality causes different phenomenal experiences in different individuals.

Idealist theories take the opposite route of physicalist theories by reducing all reality to mental reality. Idealist theories hold that physical reality is either non-existent or emergent from mental reality. By reducing the physical to the mental, idealists can explain mental causation without positing a process through which mind and body interact. Physicalist theories seem intuitive in light of the continual reduction of previously non-physical concepts to physical concepts. For expample: disease was once thought to be the result of non-physical demons or other spiritual entities but was eventually reduced to physical germs. Idealists agree that reduction is often the end-point of investigation but this reduction does not need to be to something physical. If I am playing battleships against Howard and I want to explain why my ships are being sunk. In general, it makes sense to reduce to what is immediate. Since I am only able to know that my ships have been sunk after Howard tells me which space on the board he wants to shoot, I will reduce the ships being sunk to Howard’s speech. This analogy demonstrates that reduction is most intuitive when it reduces something mediate to something immediate. Since one only knows their body through their conscious experience, the body is mediate, but the mind is immediate. For idealists, if any reduction is to be made it should reduce the physical to the mental.

One Idealist theory of note is David Chalmers’ pansychism which holds that something like mental experience is a ubiquitous aspect of reality. 2 Pansychism escapes Smart’s worry about nomological danglers since mental reality is distributed throughout all entities. This theory does not necessarily reduce physical matter, but rather reduces the conscious experience of organisms like humans to an assortment of smaller individually conscious building blocks. Pansychism manages to avoid the problems of nomological danglers, mental causation, and unintuitive reduction. There are however, serious hurdles for pansychism to overcome. If pansychism is true it remains to be seen how only certain configurations of smaller building blocks of consciousness can have experience like that of humans. Pansychism also has to somehow explain how a unified conscious experience can be broken down into component parts. Though pansychism overcomes the conceptual problems with dualist and physicalist theories, it maintains problems of its own.

Quantum concepts provide a language which could help to provide answers to the problems with physicalism, idealism, and dualism. The unintuitive reduction made by physicalism might be explained if consciousness emerges from non-local quantum characteristics of physical matter. Quantum non-locality therefore could help explain why consciousness seems unextended in physical space despite being emergent from extended matter. Idealist theories could be bolstered if subatomic particles like quarks had some phenomenal or pseudo-phenomenal characteristics. Quantum entanglement could help explain how body and mind interact on Dualist account. The uniqueness of quantum phenomena are an attractive avenue for explaining theories of mind from any position.

Quantum Optimism to Quantum Skepticism

Quantum effects such as non-locality, randomness, and superposition have immediately evident parallels to concepts in the philosophy of mind. Quantum effects are used to fill explanatory gaps in theories of mind based on these parallels. Quantum mechanics gives some theorists a scientific vocabulary with which to describe their otherwise inaccessibly abstract views. Non-locality means that entities can causally interact from a distance, which lays a groundwork for dualist pyscho-physico and physico-pyschic laws. Randomness gives idealists the chance to explain how physical reality is not predetermined. Additionally, superposition could help physicalists to deal with multiple realizability. The main issue that arises with quantum theories of mind is that they take quantum language and extend it far beyond reasonable interpretation of the scientific terms they employ. Despite this, quantum mechanics does provide interesting premises for philosophers of mind, even if it fails to provide conclusions.

Aspects of phenomenal experience such as the appearance of free choice, the existence of a mental ‘realm,’ and unified qualia are hard to square with classical mechanics. If human brains are purely matter in motion, then all future events are determined, including present and future conscious decision. Conscious experience seems to hold, on the contrary, that human beings and other conscious entities are free agents. Additionally, the thought of “a plane” seems to be quite different from the movement of matter and charge in the brain. Thoughts themselves appear in experience to have ontological existence of their own, even if they emerge from matter. The binding problem is the issue of explaining how sensory organs and brain processes create a unified conscious experience. One can explain in purely physical terms how taste buds, olfactory organs, and eyes pass information to their respective processing areas of the brain to be interpreted. The processing which takes place is however, never passed on to a central “experience” organ of the brain. So while one can explain Howard’s taste, smell, and sight while he eats an apple, one cannot explain how this experience ‘feels’ unified. There is no ‘master neuron’ where differnt sensory organs send information; the different organs of the brain process these inputs separately. The difficulty of explaining these features of conscious experience motivate the search for a new scientific basis for understanding consciousness.

While at the scale of normally perceptible objects, classical mechanics holds, the randomness of miniscule quantum entities is of interest to philosophers of mind. Upon first thought, randomness appears simple to explain: it is open and undetermined. When asked to think of a random number between 1 and 10, conscious human beings have absolutely no difficulty. Information processing machines like computers cannot however, produce random output without input. Instead, computers take variable inputs like system time or ambient noise and run them through a predetermined algorithm to create a pseudo-random output. Importantly, the output is predetermined: knowledge of all the inputs and the algorithm will mean perfect knowledge of the output. With conscious humans, knowledge of all the inputs does not mean perfect knowledge of the output. It is possible that conscious humans use something like a pseudo-randomness, generator but from common experience this is not the case. Additionally, knowing sensory inputs to a conscious human will probably allow for a better guess at what ‘random’ output they will provide in a given task. The important distinction between humans and computers is that, as far as one can demonstrate, perfect knowledge of the inputs does not mean perfect knowledge of the outputs. It is no wonder then, that philosophers would want to use the language of quantum randomness.

Philosophers like Henry Stapp use the language of quantum randomness to evidence philosophical claims about the mind. The discovery that classical mechanics does not hold at miniscule scales motivates Stapp’s argument that human thought is open and undetermined. Since quantum events can be random, so too can mental events according to Stapp.3 Extending the comparison, Stapp argues that mental events are not determined and that this therefore vindicates the common experience that conscious choice is free and open. Though this comparison between conscious randomness and quantum randomness seems intuitive, it requires a massive logical leap. It remains to be seen how randomness helps the case of free choice more than determinacy. If Howard’s choice of number is 1 rather than 9 based on quantum randomness, then he is still a slave to that random process. Stapp’s argument for free choice is one example of how philosophers of mind can step unreasonably far from quantum mechanics in their conclusions.

Before delving deeper into the failures of quantum theories of mind I will briefly explain some background and one experiment with strong implications for theory of mind. The double slit experiment and its interpretations shed light on the basic aspects of quantum mechanics that excite some philosophers of mind. The experiment was originally designed to determine whether light acted as a wave or a particle, but the experiments of note for this paper are those dealing with observer effects. The experiment involves emitting light or other entities through two slits and observing their impact on a screen. If light were a wave, one would expect to see a smooth wave pattern on the screen. If light were a particle, one would expect to see a diffraction pattern. Interestingly, if a measuring device is placed close enough to determine through which slit each particle traveled, a clump (particle diffraction) pattern is found. If however, the ‘which path information’ is not gathered, a wave pattern is left on the screen. The Copenhagen interpretation holds that the difference in pattern found on the screen is directly caused by the conscious observer’s measurement. Other interpretations hold that the difference in pattern on the screen is caused by the physical measuring device or some other cause. If observer effects caused the observed difference in the experiment it could mean that conscious thought has physical effects.

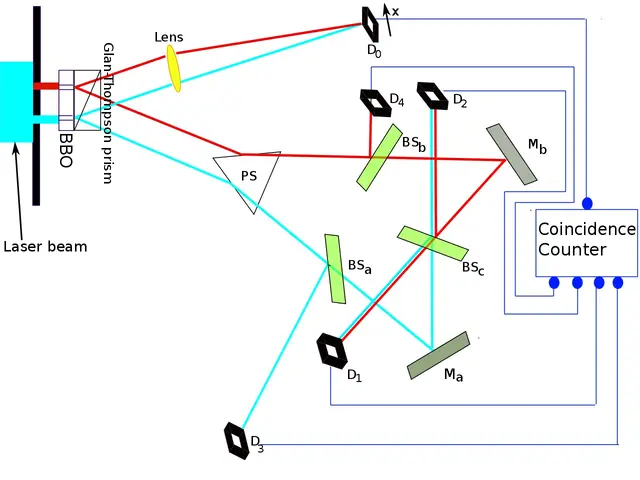

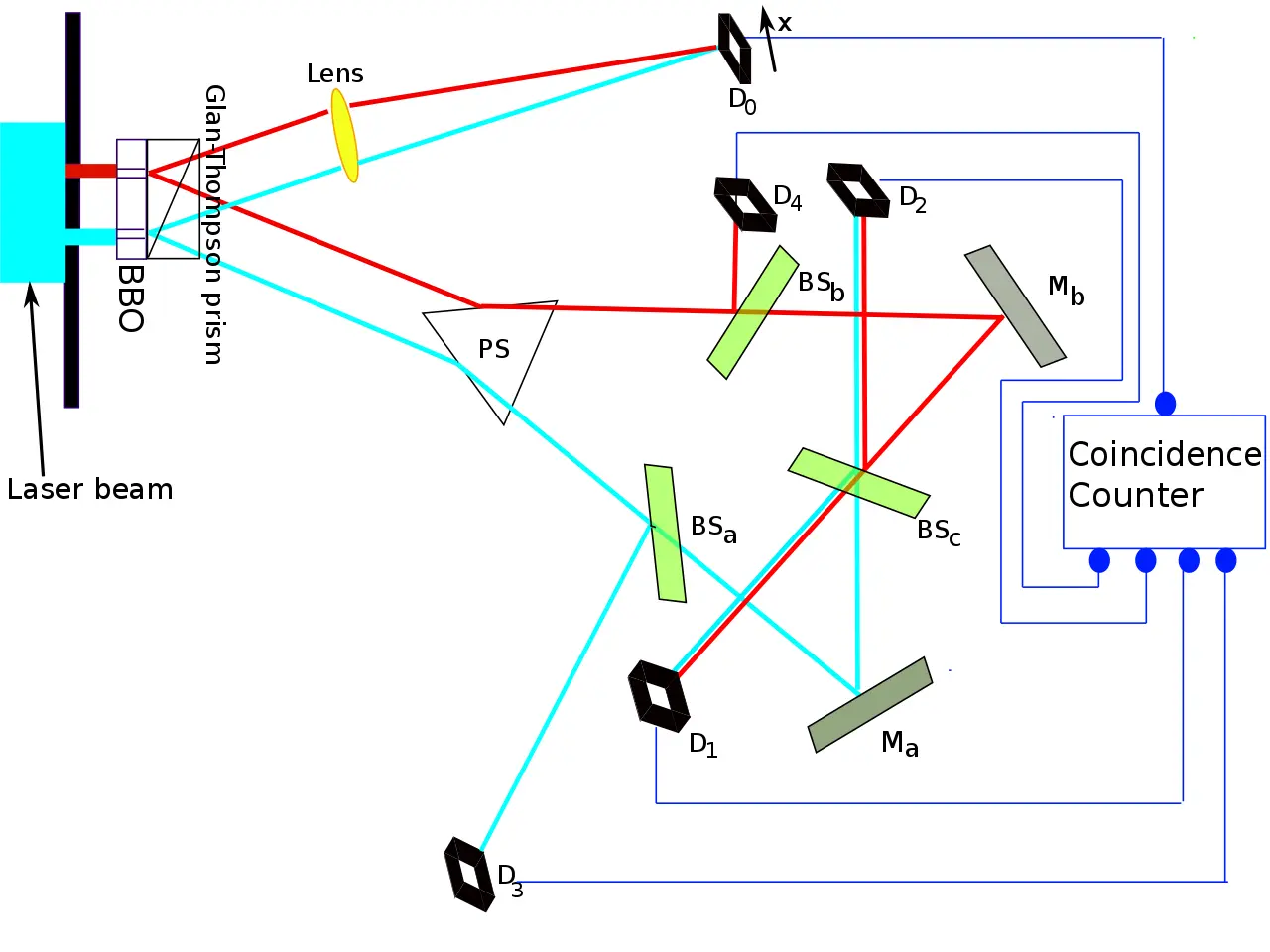

To further bolster the claim that observation produces the different outcomes in the double slit experiment, John Wheeler devised a further experiment. If photons in the double slit experiment are being collapsed into particles by the measuring device then this effect should be the same for every other entangled photon. Wheeler theorized an experiment wherein light was passed through the two slits (A and B) and further split into two entangled photons. These photons would then be measured to see if they formed a clump or wave pattern at different times. Additionally, based on the path of the photons through a series of deflectors, the which-path information would either be measured or unmeasured. John Wheeler theorized that if the measurement of a clump pattern on one photon measured later than the twin photon always coincided with the twin also forming a clump pattern, then the physical device was not responsible for the pattern. Wheeler’s delayed choice quantum erasure experiment was later conducted as shown by the image below.4

From: Patrick Edwin Moran, Delayed-choice quantum eraser. Wikipedia

As in the original experiment, photons would be emitted to pass through slits A or B (red and blue in the diagram). A crystal splits each photon into two entangled photons with one travelling to detector D0. The twin photon then continues to the second crystal (PS on the diagram) which passes photons from slit A to BSd, and photons from slit B to BSa. BSa to BSc have an equal chance of reflecting the photon or letting it pass through. The setup of the experiment means that if a photon reaches D4 then it must have travelled through slit A, and if it reaches D3 then it must have travelled through slit B. Since the photons are entangled their pattern at the detector will be identical. Additionally, the twin photons which reach D2 to D4 are measured after their twin at D0. This means that any differences in pattern found at D0 cannot be the result of the measuring device itself. Wheeler concluded that if the photons at D0 always showed a clump pattern when their twin reached D3 or D4 and a wave pattern when their twin reached D1 or D2 then it must be the conscious observers’ knowledge which determines the pattern. The researches stated that their results were an “almost ideal realization” of Wheelers theory, thereby providing strong evidence for observer effects.5

Experiments like the quantum erasure experiment demonstrate the importance of observer effects in the physical world which opens the door to new ontological categories. John Wheeler argues that since all photons which reach D0 follow the same path, the pattern they form cannot be the result of anything that happened along their path. Additionally, the path followed by the twin photon reaching D1 to D2 was only determined by their passage through the deflectors after the photon at D0 was already detected. Wheeler argued that the experiment demonstrates that a decision on earth by an observer on how to measure light from other galaxies could determine the path of photons billions of years in the past.6 If free human choices could impact the physical world, even in the past then one can explain the phenomenal experience of free will. Stapp is willing to interpret quantum mechanics in such a way as a direct refutation of determinism and as affirming free choice.7 Stapp’s argument seems to make a massive jump from observations on miniscule particles and waves to ontological claims about the human mind. Hugela and Plenio are far more cautious and argue instead that quantum effects indicate a higher probability of the existence of new ontological categories useful in describing the mind.8 The data gathered in experiments like the quantum erasure experiment are useful in demonstrating that categories like randomness, and free choice are at least plausible but do not provide much evidence beyond this.

Importantly, the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum physics upon which so many quantum theories rely, is not the only reasonable interpretation of the data. A 2016 survey of over a thousand physicists found that while Copenhagen was the most popular interpretation (39% of physicists agree) it was far from unanimous.9 In fact, other quantum concepts shed some doubt on the conclusion of theorists like Stapp. Quantum superposition means that light or other entities are not either waves or particles at any given time. A photon in superposition exists in a state of possibly being detected as a wave or as a particle. With this in mind, the quantum erasure experiment is less promising evidence for free will. If photons detected at D0 were in a superposition of exiting through slit A or B, then their collapse into a clump pattern when their twin reaches D4 or D3 does not mean that the photons passed through one slit in the past; Wheeler freely admits as much. While quantum physics provides useful avenues for comparisons to concepts in the philosophy of mind, these comparisons rely on further extending a minority view.

If a quantum theory of mind were to succeed, it must somehow convincingly link quantum effects to phenomenal experience. Penrose and Hammeroff propose just such a theory based on quantum events in microtubuli in the brain. In their view, microtubli exist at a small enough scale for quantum events to be efficacious. Building on this, they claim that microtubli activity can explain why conscious thought is so phenomenally different from computer processing. Penrose argues that thoughts are non-algorithmic and based on probabilistic quantum events in microtubli.10 Penrose and Hamerhoff have been widely criticized based largely based on the inability of their theory to explain how quantum events on a miniscule time scale can possibly cause or interact with mental states at perceptible time scales.11 Even if one accepts that quantum events are efficacious at the phenomenal level, this does not necessarily support any theory of mind. If mental states can be reduced to physical states with quantum attributes, idealists can hold that quantum events are emergent from the mind, and dualists can explain mind, body, or neither with quantum terminology. Quantum theories of mind have thus far failed to convincingly use quantum terminology to make falsifiable claims.

Quantum theories of mind are not doomed to fail simply because quantum mechanics is not fully understood. Quantum events may be efficacious in phenomenal experience and parallels between quantum mechanics and philosophy of mind should not be ignored. It is not hard to see how quantum mechanics can help a theory of mind like global workspace theory fill some explanatory gaps. Global workspace theory holds that consciousness is the posting of information from specialized brain systems to a shared ‘global workspace.’ In this view, specialized systems in the brain work to solve problems and compete to post their ‘answers.’ One area of issue with the theory is that there is no one central location to which specialized systems post their answers: the so-called ‘binding problem.’ Quantum non-locality means that entangled photons can interact from a distance. Something like entanglement might help global workspace theory explain how experience is unified from the activity of seemingly independent brain systems. Importantly, one cannot simply theorize that ‘neurons are entangled’ (a statement which makes no sense). Instead, one might use entanglement to argue that interaction between seemingly independent entities is possible in principle. Any theory of mind using current understanding of quantum mechanics must do so acknowledging the specific limitations of quantum theories. While quantum mechanics does not necessarily evidence any theory of mind, it can evidence ontological categories or processes which philosophers of mind can use as analogies to their theories.

Conclusion

The lively debate in the philosophy of mind centered around the relationship between body and mind has led to the development of convincing arguments from all sides. Physicalist, idealist, and dualist theories all have strong arguments as well as unintuitive consequences. The displacement of Newtonian mechanics by quantum mechanics has breathed new life into the debate. Quantum effects have the possibility of helping to fill explanatory gaps in many different theories of mind. Non-locality, randomness, superposition, and other quantum concepts have interesting parallels to the philosophy of mind. There are serious problems however, with trying to invoke quantum effects as an explanation or vindication of a particular theory of mind. Problems arise when theorists take concepts like quantum randomness and try to argue for conclusions far beyond the current understanding of quantum mechanics. Experiments like the quantum erasure experiment provide striking evidence for mind-to-world causality. Experiments like these are still open to interpretation and physicists are far from reaching consensus on the issues. While it is tempting to run wild with quantum effects in filling explanatory gaps in a particular theory of mind one must keep in mind that the analogies between quantum mechanics and theories of mind are only analogies. Modern physics has not disproved determinism, nor has it rendered some particular theory of mind obsolete. Quantum research does however, provide useful avenues for future research in the philosophy of mind and demonstrates in principle that explanatory gaps in existing theories might be filled.

Bibliography

Beyond Physicalism, Henry P. Stapp. 2015

David J. Chalmers, Panpyschism and Panprotopyschism. 2015

Henry Stapp in: Corradini, Antonella, and Uwe Meixner, eds. Quantum Physics Meets the Philosophy of Mind: New Essays on the Mind-Body Relation in Quantum-Theoretical Perspective. Vol. 56. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2014. Pg 7

Huelga and Plenio (2013), https://doi.org/10.1080/00405000.2013.829687.

Kim, Yoon-Ho, Rong Yu, Sergei P. Kulik, Yanhua Shih, and Marlan O. Scully. “Delayed choice” quantum eraser." Physical Review Letters 84, no. 1 (2000): 1.

Narasimhan, Ashok, and Menas C. Kafatos. “Wave particle duality, the observer and retrocausality.” In AIP conference proceedings, vol. 1841, no. 1, p. 040004. AIP Publishing LLC, 2017.

Penrose, Roger. “Mechanisms, microtubules and the mind.” Journal of Consciousness Studies 1, no. 2 (1994): 241-249.

Sivasundaram, Sujeevan, and Kristian Hvidtfelt Nielsen. “Surveying the Attitudes of Physicists Concerning Foundational Issues of Quantum Mechanics.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1612.00676 (2016). pg 11

Smart, Sensations and Brain Processes. 1959

Tegmark, Max. “Importance of quantum decoherence in brain processes.” Physical review E 61, no. 4 (2000): 4194.

Smart, Sensations and Brain Processes. 1959↩︎

David J. Chalmers, Panpyschism and Panprotopyschism. 2015↩︎

Beyond Physicalism, Henry P. Stapp. 2015↩︎

Kim, Yoon-Ho, Rong Yu, Sergei P. Kulik, Yanhua Shih, and Marlan O. Scully. “Delayed”choice” quantum eraser." Physical Review Letters 84, no. 1 (2000): 1.↩︎

ibid↩︎

Narasimhan, Ashok, and Menas C. Kafatos. “Wave particle duality, the observer and retrocausality.” In AIP conference proceedings, vol. 1841, no. 1, p. 040004. AIP Publishing LLC, 2017.↩︎

Henry Stapp in: Corradini, Antonella, and Uwe Meixner, eds. Quantum Physics Meets the Philosophy of Mind: New Essays on the Mind-Body Relation in Quantum-Theoretical Perspective. Vol. 56. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2014. Pg 7↩︎

Huelga and Plenio (2013), https://doi.org/10.1080/00405000.2013.829687.↩︎

Sivasundaram, Sujeevan, and Kristian Hvidtfelt Nielsen. “Surveying the Attitudes of Physicists Concerning Foundational Issues of Quantum Mechanics.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1612.00676 (2016). pg 11↩︎

Penrose, Roger. “Mechanisms, microtubules and the mind.” Journal of Consciousness Studies 1, no. 2 (1994): 241-249.↩︎

Tegmark, Max. “Importance of quantum decoherence in brain processes.” Physical review E 61, no. 4 (2000): 4194.↩︎